Current scenario of Arunachal Pradesh

Ever since Arunachal attained full statehood in 1987, it has gradually begun integrating with the rest of the country through a process of assimilation and major tribes have become torch bearers of Indian nationalism wearing patriotism on their sleeves.

Ever since Arunachal attained full statehood in 1987, it has gradually begun integrating with the rest of the country through a process of assimilation and major tribes have become torch bearers of Indian nationalism wearing patriotism on their sleeves.

Of course, the dominant topic of China's claim over the state as part of its South Tibet, especially its tough stance over Tawang issue (which was alleged to have been under Lhasa control for centuries) and the slow pace of infrastructure growth across the 19 sparsely populated districts of Arunachal are subjects most talked about in the state.

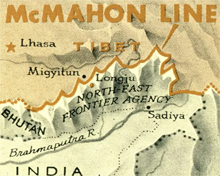

But to have a nuanced understanding of the evolution of Arunachal as a modern Indian state, we have to go back to Shimla convention 1914 when British India, Tibet and China were party to a landmark albeit controversial agreement that saw the emergence of McMahon Line, the de facto border between the India and China at present.

From NEFA to Arunachal

Before 1962, the state was known as Northeast Frontier Agency (or simply NEFA) and was an extended region of Assam.

Because of its strategic importance, it was administered by the Ministry of External Affairs until 1965 and subsequently by the Ministry of Home Affairs through the governor of Assam.

In 1972, Arunachal Pradesh was constituted as a union territory and in 1987 it became the 24th state of the Indian Union.

McMahon Line - the natural barrier

In 1913-14 representatives of China, Tibet and Britain met in India to draft a seminal convention called Shimla Accord.

In 1913-14 representatives of China, Tibet and Britain met in India to draft a seminal convention called Shimla Accord.

But the Chinese representatives refused the territory negotiation as the treaty's objective was to define the borders between the inner and outer Tibet as well as between outer Tibet and British India.

British negotiator Sir Henry McMahon drew up the 550 miles (890 km) McMahon Line as the border between British India and outer Tibet during the Shimla conference.

While the Tibetan and British officials agreed to the new McMahon line, the Chinese did not show much interest on this issue but talks broke out on identifying the boundary line between the outer and inner Tibet.

But the Chinese had no problems with the border agreement between British India and Tibet even as the latter had to cede Tawang and other areas to the Indian subcontinent.

However, the Chinese did not accept the demarcation between outer and inner Tibet and they walked out of the convention. Meanwhile, British India and Tibet went ahead with the implementation of Shimla accord and even declared that China would be deprived of any benefits accruing out of this treaty as it walk out of the convention.

At that time, China pointed out that Tibet has no independent powers to sign treaties as it was an extension of the mainland. Further, it cited the Anglo-Chinese (1906) and Anglo-Russian (1907) treaties to prove that any such agreement without the consent of China would be invalid.

In an ironical twist, the Shimla accord was initially rejected by the British India government too as it was said to be incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian convention.

But in 1921, both Russia and Britain renounced the Anglo-Russian convention. With the collapse of Chinese power in Tibet, the McMahon Line was accepted as the border line demarcating Tibet from British India.

There were no problems as no maps were published until 1935 when the civil service officer Olaf Caroe turned the focus back on McMahon line. A map published by the Survey of India showing the official boundary along the McMahon Line in 1937 was widely accepted by the officials of the British India.

There were no problems as no maps were published until 1935 when the civil service officer Olaf Caroe turned the focus back on McMahon line. A map published by the Survey of India showing the official boundary along the McMahon Line in 1937 was widely accepted by the officials of the British India.

In 1938, the British finally came out with the official record of the Shimla convention as a bilateral accord more than two decades after it was originally signed. In the same year, the Survey of India published a detailed map that included Tawang as part of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) which was administered by Assam.

The formal administrative set ups were established in 1944 in NEFA from Dirang Dzong in the west to the Walong in the east.

Tibet renews claims on Tawang

After India got Independence in late 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a letter to the Ministry of External Affairs laying claims to Tawang which is in south of the McMahon Line.

The situation became worse after the People's Republic of China (that became independent in 1949) annexed Tibet in November 1950 and India went ahead to declare McMahon has the official boundary.

In 1951, the last remnants of Tibet administration in Tawang were closed to shut shop.

China rejects McMahon Line

The newly independent PRC never recognised the McMahon as it alleged it was never a party to the Shimla convention which was forced by the colonial power to the hapless Tibet.

The newly independent PRC never recognised the McMahon as it alleged it was never a party to the Shimla convention which was forced by the colonial power to the hapless Tibet.

Further, China after taking over Tibet claimed the whole of Arunachal as part of South Tibet, most notably Tawang which was under direct control of Lhasa for sometime. The 14th Dalai Lama who ruled Tibet from 1950 to 1959 said in 2003 that Tawang was actually part of the Tibet administration before the Shimla Accord.

But he later on clarified in 2008 that Tawang is now part of India and Tibet can't claim rights over it. During the India-China war (1962), the Chinese PLA occupied all the disputed areas of NEFA including Tawang.

But they unilaterally declared a ceasefire and withdraw beyond McMahon Line thus accepting the de facto boundary as the international marker.

Sino-Indian War

All was quiet in NEFA created in 1955 as India-China relations were cordial till the outbreak of 1962 war on two fronts -- Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir) and Arunachal (eastern most).

All was quiet in NEFA created in 1955 as India-China relations were cordial till the outbreak of 1962 war on two fronts -- Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir) and Arunachal (eastern most).

While the exact reasons for the worsening of India-China relations leading to a brief war are still being debated in the media and social circles, India was thoroughly humiliated by the PLA which captured huge territories in both Ladakh and NEFA fronts.

China declared ceasefire and voluntarily withdrew from occupied areas of NEFA. But in Ladakh it had annexed Aksai Chin, a territory that India claims is under illegal occupation of China.

The brief Indo-China war resulted in the freezing of relations between the two neighbours across the Himalayas for decades.

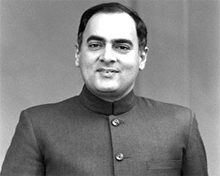

Rajiv's visit and relations thaw

Following a minor border skirmish in Sumdorong Chu Valley in 1987, then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing (1988) to cool down tempers among political leadership of China.

The Joint Working Group (JWG) was set up which held at least six rounds of talks till 1993 when PM Narasimha Rao visited China to sign a number of bilateral agreements clearing the way for normalisation of ties between the two giant neighbours.

The Joint Working Group (JWG) was set up which held at least six rounds of talks till 1993 when PM Narasimha Rao visited China to sign a number of bilateral agreements clearing the way for normalisation of ties between the two giant neighbours.

It was mutually agreed to reduce troop levels, avoid hostilities on the 4,057 km of Line of Actual Control (LAC) spread over three fronts - Western Ladakh, middle-Uttarakhand and Sikkim and eastern Arunachal Pradesh - and respect the ceasefire line till the final settlement of the border row.

High level SR-talks leading nowhere

The high-level Special Representative talks have held 18 rounds of border talks as on March 2015 with National Security Advisor (at present Ajit Doval) and Chinese State Councillor (Yang Jiechi) reviewing the earlier rounds and expressing their commitment to the three-step process to seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable resolution of the border question at an early date.

The Special Representatives have agreed to continue with their high-level talks to reach a mutually acceptable framework for resolution of the boundary question on the basis of the "Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles".